- Home

- Nick Gullo

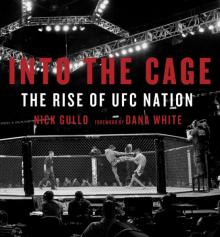

Into the Cage

Into the Cage Read online

Copyright © 2013 by Nick Gullo

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher – or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency – is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Gullo, Nick

Into the cage : the rise of UFC nation / Nick Gullo ; foreword by Dana White.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-7710-3653-8

1. Mixed martial arts. 2. UFC

(Mixed martial arts event). I. Title.

GV1102.7.M59G85 2013 796.815

C2013-900690-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013931566

Fenn/McClelland & Stewart,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited

One Toronto Street

Toronto, Ontario

M5C 2V6

www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword by Dana White

1 How Did This Happen?

2 The History of Mixed Martial Arts

3 Martial Arts Styles

4 The Hero’s Journey

5 Fight Club

6 Do the Evolution

7 The Mountain

8 Heavy Is the Crown

9 Women’s MMA

10 The Ultimate Fighter (TUF)

11 The Machine

12 Joe Rogan

13 Dana White

14 Fight Week

Photographic Captions and Credits

Acknowledgments

FOREWORD

This year marks the twentieth anniversary of the UFC. It’s been thirteen years since we bought the company, and despite all the progress, I never look back and pat myself on the shoulder. Maybe that’s why we’re successful. Lorenzo, Frank, and I know there is so much left to accomplish. That’s what we focus on.

However, when I read this slice of UFC history, and flip through the photos, I’m grateful for the fighters and fans who have helped us propel MMA into the fastest-growing sport in the world.

Nick is one of my closest friends. With his unprecedented access he’s crafted something truly unique. As he emphasizes throughout this book, the fighter’s journey is a metaphor for life. We all start at the bottom. We all face adversity. But when we bow our heads and work through the hardships, refuse to surrender despite our doubts, we grow stronger. And growing stronger, we prevail. That’s the journey of a champion.

Enjoy.

Dana White

UFC President

1: HOW DID THIS HAPPEN?

Liz Carmouche, first challenger to the UFC women’s bantamweight belt, UFC 157.

IT STARTED WITH A WHISPER. More than ever I’m convinced it always starts with a whisper…

Walking down the corridor, I hear music echoing through the walls, the crowd chanting, announcers hyping the main card—but this isn’t how or when it started. This is 2008, which is somewhat of a way station in this tale, and where we are is inside a concrete tunnel beneath the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas. Cramped quarters. Fluorescent gray light distorts shadows. A metal duct overhead spews cold air, but it’s no comfort. I’m sweating, nervous. Dana White turns and flashes that iconic grin, and for a moment it’s like old times—like we’re teenagers again, ready to knock heads. “You cool?” he says.

I shrug, trying to play it off, like what waits beyond this tunnel is nothing, just a midday stroll through an empty stadium. Never mind the twelve thousand rabid fans.

No. I’m anything but cool. My stomach’s rumbling and I’ve got this taste on my tongue, like I downed a glass of questionable milk and next I’ll vomit in that passing can. But, like, pull it together, dude, because they—the PR lady to my left, the assistant holding a clipboard and a walkie-talkie, the camera guy—are all staring, and I know they’re thinking, Who is this guy? If they’re such good friends, where the fuck has he been?

And yeah, they’re right to question. It’s been eight years since Dana and I last saw each other.

Eight. Years.

Flip back through the calendar and that lands us premillennium. Since then, the world’s endured hanging chads, planes careening into towers, green missile flares over Iraq, a foreclosure crisis. The last time Dana and I were together was on a return flight to Vegas. Here’s the scene unfolding: I’m munching pretzels while Dana flips through a mixed martial arts (MMA) magazine. After some turbulence he leans in and whispers something. What’s that? Oh, he’s mumbling about MMA, how it could be the next thing. Clouds pass outside the window and I’m hardly listening. I’ve got pressing concerns, like should I move my young family to the Gulf Coast, swap the Vegas desert for Florida’s sandy beaches, abandon friends, and—

“I’m telling you, bro, this could be big,” he says.

I glance at the article and give him a curt nod, but I know this won’t appease him. Once Dana gets something in his head—whether it’s a new “system” for beating the roulette wheel, a hot parlay for Sunday’s games, or a guy who crossed him—forget it, you might as well toe the line. “Looks great,” I say and turn back to the window.

“I’m fucking serious,” he says.

“Yeah, all right, I heard you—huge. It could be huge.”

“Asshole.”

Okay. This clearly wasn’t going to end. “What do you mean?” I say. “Like kickboxing? Or those strong-man competitions where they drag logs through the mud?”

“No, dipshit, a cage, they fight in a cage.”

“Ohhh, tough-guy matches—didn’t Mr. T win one of those?”

“You’re a gorilla.”

Of course in hindsight, I’m the idiot. Hurl the black roses, I’ll gather them all. In retrospect, this exchange is akin to Moses preaching from the mount while some fool snickers and polishes the golden calf. But understand, Dana and I were friends, and what did he know about MMA? Back then he was teaching casino executives and their wives to sidestep and throw jabs, paying the family bills as a boxing coach. Yeah, on the side he managed Tito Ortiz, a cage fighter, so there was at least a tacit connection with this new obsession—but still, to my ears, the phrase MMA elicited two events: first, the legendary 1976 Muhammad Ali versus Antonio Inoki bout, wherein the champ flew to Japan and fought under hybrid rules that allowed kicking but no grappling, jabbing but no flying knees, and resulted in an absolute farce, with Inoki on his back much of the fight, throwing heels and flailing like a tempestuous child, for which Ali suffered blood clots in his leg that threatened amputation and hobbled him for the rest of his career; and second, in 1993, the first Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) on pay-per-view (PPV).

Everyone I knew tuned in to this inaugural UFC event, all of us frothing at the prospect of various disciplines clashing in the ring: kung fu versus boxing versus Krav Maga versus sambo. Mind you, these were the heady days of Mortal Kombat and Virtua Fighter, the arcades packed with kids—no, not just kids, also grown men—battling as Kung Lao, Liu Kang, and Kage-Maru. So after forking over fifty dollars for the PPV, we expected blitzkrieg action. Bruce Lee scissor kicks. Multi-hit combos. Fatalities!

Instead, we endured two hours of mismatched fighters, untrained camerawork, and hairband synth music. Yeah, there were some exciting moments, and yeah, Royce Gracie’s Brazilian jiu-jitsu was impeccable, and yeah, he dominated all comers, and yeah, yeah, yeah, the core fans mythologize that first event and swear it was the greatest thing since Hagler versus Hearns—but to my untrained eyes all that ma

t work was akin to a typical high school wrestling match … and I was a lifelong wrestler!

Now, I know to some, the most devoted, this screams of heresy, but watch those early events and you’ll see that the production value is just a notch above early 1980s Betamax porn. Scan the replays and note Art Jimmerson feinting with a single boxing glove during his bout with Gracie, which lasted all of two minutes before Gracie wrestled the hapless boxer to the ground and submitted him. This is a prime example of a bout that elicited pre-bell whoops and whistles and post-bell groans.

And check out the morbidly obese Teila Tuli sumo-charging across the ring at karate/savate champion Gerard Gordeau: Gordeau casually steps aside, Tuli crashes into the cage, falls to his knees, receives a kick in the face, and his tooth flies to the mat. At twenty-six seconds, the referee steps in, waving his hands. Now, while that was humorous, can you imagine such a hokey matchup today? And the good fights? Well, most of us didn’t know how to watch them.

Here’s Ken Shamrock summarizing one of his UFC 1 victories as a shootfighter/wrestler, which came at just 1:49 after the opening bell: “I was fighting Patrick Smith. He’s 250–0 in bare-knuckle fights. He’s undefeated. I remember the bell rings, I go in there, and Patrick throws a hard kick. I shoot on him. I take him down. I punch him a few times. I drop back down to a heel hook. I crank his heel, I break his leg. AGHHHHH! The crowd booed. They were mad. No one understood what submissions were! They were like, ‘What was that?’ Even the announcers were like, ‘He got him in, uh, some, uh, foot lock, or something …’ It was like no one knew. They didn’t have an idea. Royce Gracie and myself were the only ones that really knew what submissions were, knew how to do submissions effectively in a real fight.”

I think I’m on safe ground asserting that jiu-jitsu, like wrestling or judo, requires the audience to possess at least a basic understanding of the subtle strategies at work; and unfortunately, many of us watching that first event expected everything but fighters rolling across the mat for extended periods. And once they were down, we certainly didn’t grasp what was happening.

So, no, I didn’t imagine the sport growing into anything beyond its back-room status, much less huge.

Fast-forward five years from that plane flight: I’m in Florida, working, surfing, raising our daughter—only there’s no cable television in the house (as in no CNN, no sports, no pay events, no reality TV. Nothing.) How such a thing happens is that the wife finds your young daughter lifeless in front of the television again and again, eyes glazed and thumb on the remote, and being an overprotective mother she pulls the plug and allows only DVDS through the front door. (To be fair, there was reason to worry. Once during dinner I spilled red wine on the rug and while my wife fretted with a spray bottle and towel, from nowhere our daughter blurted, “Oh, Mommy, don’t worry about that stain. You can Zap it out! Zap removes coffee, wine, cherries, even blood!”)

So yeah, choosing my battles I conceded to the crackdown, which meant I’m not just across the country, I’m on a veritable desert island. But I heard things. Such as Dana whispering that mantra to Lorenzo Fertitta, another high school friend: “I’m telling you, bro, this thing could be big …”

Only Lorenzo listened, and with his older brother, Frank, they purchased the ailing UFC and installed Dana as president in 2001. But that’s it. No clue how it was doing. Occasionally I received a Dana email exhorting me to visit, but I was slammed with life and work and just never found time to venture from the shore. That is, until the monstrous hand of God, in the form of Hurricane Katrina, swept through the Gulf of Mexico in 2005 and mangled the entire coast.

Cataclysm doesn’t even begin to describe such an event, not at your doorstep.

We interpreted the signs, packed our vintage Airstream, and drove away from the debris, touring the country and eventually winding our way back West. Once in Vegas, I surprised my old friend with a phone call. He picked me up in a black Range Rover. I rubbed his bald head and hugged him. “It’s been a long time, Gorilla,” he said.

“I can’t believe it,” I said. “Tell me everything.”

Now, nearing the black curtain at the mouth of the tunnel, the floor thumps with every step, but how it feels is like I just swallowed the red pill and that’s why I’ve got these cold sweats. Welcome to the real. One moment I’m on the plane with my bro, close my eyes, and now—

Security guards surround us. A hand drops on my shoulder and passes me a laminated badge, UFC 84: Penn vs. Sherk. I stare at the flimsy rectangle and try to tune out the screeching walkie-talkies.

“You cool?” Dana again asks.

I grip the badge like a talisman and smile back. “I’m cool.”

“Let’s go.” The drapes swing wide and we’re rushed into darkness, shoved into limbs, bodies, bodies everywhere. Security clears a rough path. We round a barricade and a spotlight ignites. The crowd erupts. Cameras flash and I’m feeling my way … finally the splotches clear, and oh shit, he’s gone. Swallowed whole. I’m knocked into a gate. Massive LCD monitors hang from the ceiling, and wait, there’s Dana floating overhead, that bald head bigger than I could ever imagine.

It’s too much. I let him go, knowing we’ll catch up at the press conference. Chuckling to myself, I remember us drinking beer and slam-dancing to punk music in his bedroom—and what I wonder, what I can’t fathom, is not how such a ridiculous idea inspired a whisper, but how a whisper grows so fucking deafening.

The facts. Trawling the web yields some neat-ish stats: MMA is the fastest-growing sport in the world (according to Simmons Research Database, gate attendance at UFC events from 2001 to 2008 increased more than 500 percent. Further, between 2005 and 2008, the fan bases of the NFL, NBA, MLB, MLS, and NASCAR each declined, while the UFC fan base increased more than 30 percent); UFC bouts typically draw 12,000 to 15,000 attendees and, according to third-party guestimates, upwards of 1.6 million PPV buys; The Ultimate Fighter reality TV series often attracts more than 1 million eyeballs; fights are broadcast in more than 145 countries and territories, and the UFC boasts 31 million fans in the United States and 65 million worldwide; hundreds of MMA companies, responsible for thousands of jobs, attend the UFC Fan expo twice a year; the UFC Undisputed 2009 video game sold more than 3.5 million copies upon its release; UFC Octagon girl Arianny Celeste has graced the pages of Playboy, Maxim, FHM, and The Atlantic; most major news outlets cover MMA, with staff journalists cranking out the who/what/when/where/why of every MMA murmur and happening—

But enough already, as this is neither a MMA encyclopedia nor a Dana White biography—there’s plenty enough compendiums and sites devoted to individual fighter stats, and as far as a bio, though I’ve injected plenty of D.W. anecdotes and history throughout this book, his bio is another project. So what you’re holding here is my attempt to chronicle, and I hope make sense of, the maelstrom that he, Lorenzo, and Frank unleashed on our post-millennium world.

Some nights, usually after a stiff glass, I hear that whisper. So I break out the album and sift through old photos. Fuck yeah, I find it strange. Then, now. There, here. And in those moments, what I want more than anything is to raise my drink and for real swallow the red pill, just to see how deep this rabbit hole goes.

Before the fight.

2: THE HISTORY OF MIXED MARTIAL ARTS

UFC 1 poster.

“The ending is nearer than you think, and it is already written. All that we have left to choose is the correct moment to begin.”

—ALAN MOORE, V FOR VENDETTA

THE EARLIEST ACCOUNTS of competitive combat reside in stone carvings, oral histories, and literature. Egyptian hieroglyphs depict soldiers boxing, while Greek mythology tells us the god Apollo invented sport-grappling when he fought Forvanta, a prince chosen to represent humanity. Of course Apollo easily pummeled Forvanta to death, but, hey, the man’s legend persists. Even Homer jumped on the bandwagon with The Iliad, when at Patroclus’s funeral games, Epeus and Euryalus fought for a prized mule. But it’s the 23rd Ol

ympic Games in 688 B.C. that provide verifiable records of a primitive form of boxing, and the 648 B.C. Games that boast the sport of pankration, a combination of boxing and wrestling similar to today’s mixed martial arts.

These early celebrations of competitive combat mirror our current fascination with MMA. Just as we lionize our champions, the ancient Greeks also revered their fighters. Take Theogenes, the first athlete to earn Olympic gold in both boxing and pankration. Over two decades the legendary pugilist defeated more than fourteen hundred opponents. Of course he probably fought his share of squibs—weaklings thrown into the arena to entertain royal partygoers—but still, given the streak, given the Olympic laurels, it’s hard not to crown Theogenes the godfather of MMA. Throughout his life fans erected statues to honor him, and following his death they worshipped him as a healing deity.

Post-Theogenes, let’s drop in on Alexander the Great just as he invades India, circa 326 B.C., bringing with him not only swords and archery but also Greek culture: art, cuisine, mythology, sporting events—including pankration. Buddhist monks, chilling in their temples, watched the army practice pankration in the village square. They watched and learned, keen on the unarmed combat because their honor system prohibited the use of weapons. Records from the era are scant, so from here it’s a matter of conjecture. A predominant theory holds that over decades these monks drilled the techniques and, applying their knowledge of anatomy and momentum, evolved the “sport” into something more subtle, more deadly, thus birthing the art of jiu-jitsu.

The sun scorches, the sky is vast, and monks wander. From India our monks roamed the Asian spice routes, arrived in China, and taught their brethren the art. Chinese practitioners ferried the techniques across the East China Sea, and once in Japan, jiu-jitsu embedded itself into the country’s martial arts culture.

At least that’s what we think. What we know is that in 1532 Hisamori Takenouchi, a samurai from the famed Takeda clan, opened the first Japanese jiu-jitsu school, and four centuries later Otavio Mitsuyo Maeda, a Japanese businessman, moved to Brazil and there taught Carlos Gracie the art of jiu-jitsu. Carlos taught his brothers, and Gracie jiu-jitsu (also called Brazilian jiu-jitsu, or BJJ)—the forebear of modern MMA—was born.

Into the Cage

Into the Cage